I love the expression “sudden death.” It refers to a FIFA tie-breaking rule last used in 2002, when South Korea and Japan hosted the World Cup, but most of matches in this year’s El Mundial, as the games are known to Spanish-language viewers of Univision, all felt like sudden death, at least in the round of 16, which concluded Tuesday. (By the way, Univision’s newscast has been far superior to ESPN’s, at least at the level of wordplay.) The Netherlands-Mexico match was a nail-biter (I’m Mexican!), as was Costa Rica vs. Greece. Watching these games is like reading a superb thriller: Tension is high and time seems to stand still.

Like much of the rest of humanity (according to various sources, half of the globe’s population is tuning in), I wait—patiently!—four years for this fiesta. This one in Brazil is among the best I’ve seen, and I’m watching every minute of it. This is the life for an academic: finding ideas even in leisure. To study what? The way Brazilians throw a party? Whether countries’ uniform styles, or their varied goal celebrations, reflect ethnic and nationalistic identities?

Seriously, the World Cup provides a range of topics for scholars to consider: Governance. Economics. Justice and morality. Theater. Masculinity. Not to mention the layers of meaning in carnival, carnaval do futebol in Portuguese. Let me ponder them one by one:

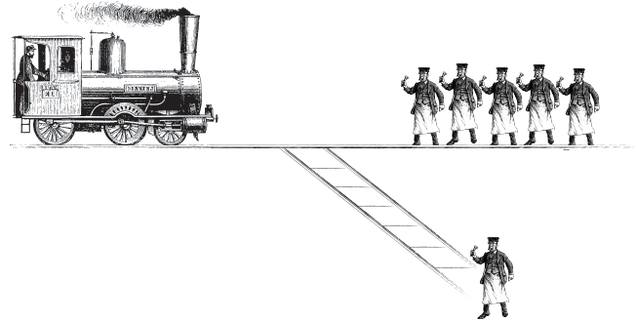

Governance. There might be 22 players on the field, but only one person matters in a game, and it isn’t one of the players. It is the referee. He is the judge, the pardoner, the decider. Teams compete to score the most goals, but they also work on the ref. He might be objective. But you know—everyone does—that there is no such thing as objectivity.

The ref’s authority is bestowed upon him by FIFA, world football’s governing body. To participate, all parties must adhere to its rules. It is a true international body, like the UN, the EU, or the Group of Eight. Unlike in those entities, however, no country exerts more power in, or more influence over FIFA. That makes the World Cup illustrious. This is a stage in which small nations like Chile (population: 17.5 million) are as important as France (65.7 million), Russia (143.5 million), and the United States (313.9 million). They all abide by the same rules. They dress the same way. They play the same number of games. Is this a model for global equality, or what? Obviously, finding a champion, whose reign lasts four years, is the purpose. But what does being the winner mean? Nada, really. It is about reputation, not about control.

FIFA is often criticized for being corrupt. And it is. The controversy over the Qatar games in 2022 are proof. Governance is never pure. Yet the World Cup is the best example I know of authentic, peaceful coexistence at the global level. Plus, as I wrote recently in The New Republic, the World Cup is God’s way of teaching people geography, getting us out of our cocoons—making us realize, as ET said, that, yep, we aren’t alone.

Economics. We might think the World Cup is all grand spectacle, but it is also a marketplace of ability. Established players already play in La Liga, the Premier League, and on other important stages. Younger talent makes a splash, hoping to command top dollar, while high-end scouts appreciate—and, when needed, depreciate—those players’ value.

“Value” is the crucial word. What we see is worth money. Not only on the field. The host nation capitalizes on its investment by bringing tourists from everywhere. Billions are spent on broadcasting. The Brazilian smiles on the TV screen are lessons in joie de vivre. But value is also measured in spiritual power. Are the spirits favoring one team or the other? What voodoo practices must be performed to motivate a higher force to bring down an opponent? The value of certain religious practices is thus critical, showcasing how the material and spiritual realms are intertwined.

Justice and morality. Some games are Shakespearean. Like when Zinedine Zidane of France head-butted the Italian player Marco Materazzi in the 2006 final for insulting his sister—clearly, there is one thing more important than winning a World Cup, and that is honor. Or in the Uruguay-Ghana match of 2010, when Luis Suárez of Uruguay stopped a strike by Ghana with his hand. The goal would have eliminated Uruguay. Suárez was expelled, and Ghana got a penalty kick. But the striker missed, making Suárez a hero.

Real life isn’t fair. Neither is soccer. Moral decisions make each game a battle between good and evil. How do players reach a decision? Is it possible to balance reason and impulse?

Suárez is again suspended, this season for biting an Italian player. This is the third time he has engaged in such unsportsmanlike behavior, and he was punished the previous two times. He has now been banned from four months of play in FIFA matches. Suárez, in my view, suffers from mental illness. The biting wasn’t designed to push the game in a particular direction. He simply lost control. On the surface, his action doesn’t have much to do with morality. If he does warrant a psychiatric diagnosis, perhaps FIFA should use the incident to alert fans about the mental anguish players face during a match. Óscar Tabárez, the Uruguayan coach, bitterly complained after the incident, saying “this is about football, not about morality.” Most of the world did see it as immoral, or at least uncivilized. Yet Uruguayan fans agreed with Tabárez, saying—in a paranoid mode—that FIFA was after them.

So the World Cup is like a Dostoyevsky novel. When is a sinner an actual sinner? Is defending one’s honor as justified as Rashkolnikov’s killing of Alyona Ivanovna, an abusive old money-lender?

Theater. A graduate student could write a dissertation on the dramatic talents of World Cup players. Most must have taken a course, not only in pantomime but in melodrama. I haven’t seen any statistics, but the number of histrionic dives in the tournament seems considerably higher than in previous World Cups.

The king of them all—a veritable master of the art of pretending to suffer—is the Netherlands striker Arjen Robben. In the Netherlands-Mexico match, he worked the ref, Pedro Proença of Portugal, to exhaustion—until he finally got what he wanted: a penalty kick at a crucial point. Lo and behold, Holland converted it into a 2-1 win.

Americans dislike the theatrics, and, believe me, Mexicans were unhappy with Robben’s action. But life, like I said, is a spectacle, and fútbol, as Hamlet said of poetry, “holds the mirror up to nature, to show virtue her own feature.”

Masculinity. Where else does one see 25 vigorous males on the field (counting the three referees) for an hour and a half, all in short pants, running, kicking, jumping, touching each other, doing all sorts of pirouettes, and competing to see who puts the ball in the net more often? None of these men is accused of being gay—not even Ronaldo, the Portuguese superstar, who loves taking his shirt off after scoring a goal and flexing his muscles. Are gender boundaries more flexible during the World Cup?

Subversion. Stereotypes are a dime a dozen in El Mundial. To start with, nationalism is pushed to its limit. Just look at the stands. Fans, scores of them, dress in their country’s flags, their faces plastered with the colors. They scream and shout patriotic slogans, cursing other nations. I cannot think of another forum where nationalism is as excessive. It is all in the spirit of partying, of course. And, in that context, becoming a stereotype is useful. Colombians show up as coffee makers, Mexicans as mariachis and Frida Kahlos, the Greeks come in togas, Italians as Luciano Pavarottis, Americans dress like Uncle Sam. Everything you ever hated about your own background is now beyond criticism. What does this say about respect and intellectual freedom? A lot. For the World Cup—and the one in Brazil for sure—is, as I mentioned, a carnaval, meaning it embraces subversion, turning it into a commodity. You can say whatever you want during those five weeks, you can pretend to be who you’re not, you can cry in public, as long as it is done in an atmosphere of camaraderie.

Social media’s role has been more important than in the past. Every match prompts endless tweets. The email conversations I have with friends around the globe are inspiring. Every major incident on the TV screen is accompanied by images Photoshopped in a matter of seconds, as when Memo Ochoa, the Mexican goalie, stopped an onslaught of attacks from Brazil and Holland. I received his image superimposed to the Corcovado, atop which stands the legendary statue of Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro. Or superimposed on a portrait of Neo in The Matrix.

Frankly, we academics are boring in comparison! We aren’t used to this much excitement, to the “sudden death”-like drama. El Mundial is fertile ground for academic, not to mention classroom, reflection. Let us wake up from our stupor and turn to this raw material.

On Thursday, in the National League Championship Series game between San Francisco Giants and the St. Lous Cardinals, Giants outfiender Travis Ishikawa came to bat in the bottom of the ninth inning.

On Thursday, in the National League Championship Series game between San Francisco Giants and the St. Lous Cardinals, Giants outfiender Travis Ishikawa came to bat in the bottom of the ninth inning.